|

| |

Although ground vibration standards have been available in the U.S. for some vibration sources (e.g. blasting) since at least the 1970's, most

U.S. states and municipalities still have poorly-formulated or no regulation of damage-causing

vibration from construction. Yet, the sheer amount of damage done in construction settings alone (see below) suggests a keen need for some oversight and control of vibration from construction. Although ground vibration standards have been available in the U.S. for some vibration sources (e.g. blasting) since at least the 1970's, most

U.S. states and municipalities still have poorly-formulated or no regulation of damage-causing

vibration from construction. Yet, the sheer amount of damage done in construction settings alone (see below) suggests a keen need for some oversight and control of vibration from construction.

Here, I'll discuss some considerations in establishing meaningful vibration regulations

and limits which, if followed, can largely prevent mostly unnecessary damage from construction vibration, saving untold money and annoyance for homeowners, contractors and project sponsors. Such common sense regulation can help reduce damage-related litigation and maintain good relationships with

nearby property owners, at little or no additional cost to the project sponsor or the contractor, once put in place. Why Regulation Is Needed Property owners need special consideration and protection in the regulatory process, because

they usually lack the knowledge, experience, scientific understanding, money and legal

power to approach vibration damage incidence on a par with those who may be responsible

for it. Home and building owners with legitimate and extensive damage claims are too often left with no other option but to seek recourse

in the legal system. It's a good bet that, if there is

substantial damage to one home, there will be damage to others, further burdening the legal system.

Regulators must

consider the rights of the uninvolved third party (the home or building owner) to

proper evaluation and mitigation of risk of damage to his property, as well as

issues perhaps more properly characterized as nuisances (noise, non-damaging

vibration, disruption of lifestyle, blockage of streets, etc.). They must balance the homeowner's rights to use and enjoyment of his property against the very considerable economic, governmental and societal pressures to

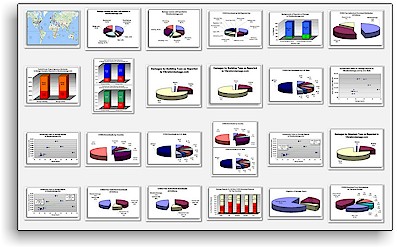

complete projects as cheaply, quickly and, yes, profitably, as possible.  The risk of ground vibration damage to homes and buildings is analyzed statistically in the CVDG Pro chapter, Damage Statistics, using

data from over 2800 registrations of the much less comprehensive CVDG free version e-book (see graphic at right for some examples). As of this writing (November 2023), there have been CVDG e-book

registrations from the United States and over 100 other countries. Explicit damage-related registrations (Damage to home, Damage to building, Legal) have been received from over 70 of those non-U.S. countries. There are more examples from registrations where the

primary reason for registration was something other than damage (e.g. Consultant use), but the person indicated in his comments that damage to a structure was involved. In the U.S., registrations embrace every state and D.C., plus several of the

U.S. territories, while explicit damage registrations include all but one state, along with

some of the territories. The risk of ground vibration damage to homes and buildings is analyzed statistically in the CVDG Pro chapter, Damage Statistics, using

data from over 2800 registrations of the much less comprehensive CVDG free version e-book (see graphic at right for some examples). As of this writing (November 2023), there have been CVDG e-book

registrations from the United States and over 100 other countries. Explicit damage-related registrations (Damage to home, Damage to building, Legal) have been received from over 70 of those non-U.S. countries. There are more examples from registrations where the

primary reason for registration was something other than damage (e.g. Consultant use), but the person indicated in his comments that damage to a structure was involved. In the U.S., registrations embrace every state and D.C., plus several of the

U.S. territories, while explicit damage registrations include all but one state, along with

some of the territories. There are no statistically significant changes in the ratio of damage-related to non-damage registrations of the CVDG over the period from 2014 to 2022.[37] These data indicate a clear and ongoing worldwide problem

with construction vibration damage to structures. Regulators, especially those with direct control over local work, can mitigate it by setting and enforcing standards which reflect the true risk to existing structures posed by construction.[6] The Role of Ground Vibration Standards  Vibration standards

and limits are, by nature, a regulatory concern, as they provide the means by which

scientifically-defensible regulation can be put forward and implemented. As discussed at length in the CVDG chapter,

Vibration Standards, some national, state and municipal governmental and industry groups around the world have set ground vibration standards and limits in at least

some vibration settings.[1] National standards are usually based on scientific studies, even if they don't cover well all potential

vibration sources and environments.[2] Vibration standards

and limits are, by nature, a regulatory concern, as they provide the means by which

scientifically-defensible regulation can be put forward and implemented. As discussed at length in the CVDG chapter,

Vibration Standards, some national, state and municipal governmental and industry groups around the world have set ground vibration standards and limits in at least

some vibration settings.[1] National standards are usually based on scientific studies, even if they don't cover well all potential

vibration sources and environments.[2]

Vibration Standards

in the free CVDG has an extensive analysis of the meaning, limitations, interpretation, vibration velocity limit values, and proper use of

existing vibration standards

in various ground vibration settings. It also provides a summary of the national standards in place around the world and discusses that subset of ground vibration standards which are most influential in research and most used worldwide. Reading

that chapter is essential for anyone who will set or use ground vibration standards in their work. The CVDG's Vibration and Damage chapter provides information on vibration: human

perception of it, its

effect on structures, probabilities of damage, and the ways in which vibration damage is characterized and categorized. The CDVG's Vibration Potential chapter will give the

regulator a quick view of the types of construction operations which need special attention. Reading those chapters will help the regulator understand what needs to be regulated and why. State and Local Regulation of Vibration State and municipal vibration standards, when they exist at all, are highly variable

in their coverage and value. Yet, it is those standards which can have the most impact in avoiding vibration damage, since compliance can be more readily ensured locally. Sadly, there are too few states,[33] cities and

towns which have set meaningful, reliable and scientifically-supportable ground vibration standards, which recognize and take into account both the damage potential differences between vibration sources and variations in vibration propagation from

locale to locale.[22] Some of the few state and local entities which have any vibration regulations may have arrived at them on weak or improper scientific grounds, often with the advice of "experts" who may not be

knowledgeable,

or even entirely unbiased, about construction-related vibration damage. Some of those bodies may not enforce, or even have any means to enforce, the regulations they have. The relative scarcity of state and municipal standards in the U.S. significantly limits how much

how much can be done to

prevent damage meaningfully.[32] The result is unnecessary

damage, expensive litigation and loss of citizen goodwill. Regulation of Construction Vibration

Well-researched, properly chosen and applied vibration standards are an important part

of the regulatory picture. However, effective regulation must

accurately reflect scientific understanding of the real risks and, more importantly in

the construction vibration case, the considerable differences between construction vibration characteristics and those of the better-studied blasting vibration. Too

many times, standards are chosen which are simply inappropriate for construction

vibration (e.g. use of blasting standards in non-blasting construction

environments); there is little or no defensible scientific basis for them. Their use in construction settings is directly contradicted by statements in the original blasting studies, which are the basis for those blasting

standards. Often, the choice of a standard is based mostly or solely on input from "experts" whose livelihood

depends to a large degree on the construction industry or whose real expertise, if any, is blasting vibration, not long duration heavy equipment-caused construction vibration. Even for short duration, relatively well-studied blasting vibrations,

potentially damaging "racking"

vibrations at wall penetration corners can be subject to amplifications of up to factors of four in homes for blasting-caused vibrations.[17] If we apply the mid-frequency 0.75 in/sec OSM ground vibration blasting limit and amplify it by a factor

of four in accordance with the known home resonant amplification, we get a home corner velocity of 3.0 in/sec, a velocity capable of opening butt joints in drywall.[18] Although amplifications for long duration

(typically, minutes to hours) vibrations in construction settings are largely, if not completely, unknown, it is highly likely that they would be at least as high as those in short duration ("a few seconds")

blasting events.[35] Thus,

any construction project inappropriately using and meeting the OSM blasting standard would have, at the least, an unacceptably high likelihood of causing drywall joint opening in the closest surrounding homes.[15]

As is discussed in many other locations in the CVDG and CVDG Pro, blasting vibration

often differs

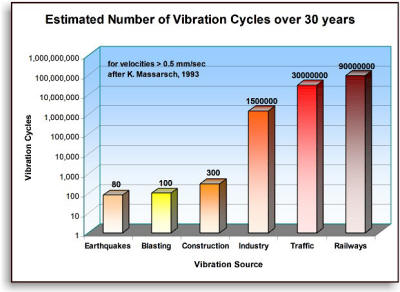

in just about every important way (duration, frequency distribution, repetition number and rate) from construction vibration. Some approximate repetition estimates are shown in the diagram, scaled logarithmically, for various types of

vibration sources. These numbers, while very approximate, illustrate just one of the reasons why blasting vibration standards should not be used for other vibration sources, based solely on the

number of repetitions experienced by structures.[34] As is discussed in many other locations in the CVDG and CVDG Pro, blasting vibration

often differs

in just about every important way (duration, frequency distribution, repetition number and rate) from construction vibration. Some approximate repetition estimates are shown in the diagram, scaled logarithmically, for various types of

vibration sources. These numbers, while very approximate, illustrate just one of the reasons why blasting vibration standards should not be used for other vibration sources, based solely on the

number of repetitions experienced by structures.[34]

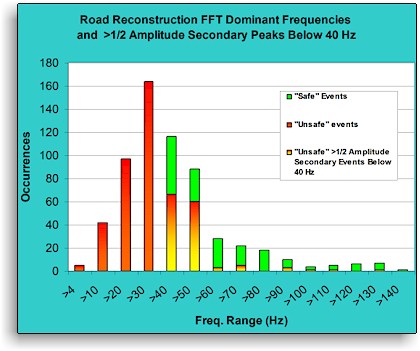

The diagram at right shows the actual observed dominant Fast Fourier Transform-derived frequencies of vibrations from

heavy equipment use in a road reconstruction

job, along with those dominant peaks in the vibration spectra which are above 40 Hz in frequency, but have secondary peaks below 40 Hz which are 1/2 or more in amplitude of the dominant frequency.[7] The diagram shows that construction vibration in this job had most of its overall intensity at

frequencies below 40 Hz, i.e. in the regime most damaging to homes and other structures.[7],[8]

These, and other, disparities mean that blasting vibration standards are

generally not useful for construction vibration regulation, nor are their use in such environments defensible scientifically, even though the results of some parts of blasting vibration studies can be very useful in understanding vibration

effects on homes and other structures. These, and other, disparities mean that blasting vibration standards are

generally not useful for construction vibration regulation, nor are their use in such environments defensible scientifically, even though the results of some parts of blasting vibration studies can be very useful in understanding vibration

effects on homes and other structures. By way of illustration of how setting inappropriate standards can lead to damage, consider that it has been stated in the scientific literature with regard to the Swiss machines and

traffic standards that damage is "to be expected" at twice the Swiss limits.[30] For a Class III, timber-framed home of the type common in the U.S.,

the Swiss standard is 0.2 in/sec (numerically the same as the U.S. FTA standard). Thus, at 0.4 in/sec, damage would be expected. The lowest blasting standard in the U.S., suggested in USBM RI 8507, but not adopted by OSM, is 0.5 in/sec in the same frequency range. The OSM

standard at mid-frequencies is 0.75 in/sec, nearly four times the Swiss Class III limit. Thus, we would expect damage to be highly likely when blasting standards are inappropriately applied and barely met, let alone

when exceeded, in construction situations involving heavy equipment use.[31]

Setting Effective

Local Vibration Regulations Most people would probably accept that one goal of vibration regulation is to prevent most, if not virtually all, damage, while allowing vibration-causing

activities (blasting, heavy equipment use, etc.) to proceed without unreasonable burdens, both financial and regulatory. Some small financial obligations, e.g. in the range of 0.1-1.0% of the total project cost, should be considered reasonable and part of the cost of

doing business, if they can prevent potentially millions of dollars in damage to surrounding property and even higher litigation costs.[5] Good regulations will achieve a balance between preventing

unnecessary, expensive damage and

the cost of implementation. Putting forth regulations designed only to allow contractors to work with little or no impact from the regulations is not a balanced approach, nor is it likely to be an effective one.  Existing national standards can be a useful guide in setting local standards. One can even set local or regional standards by referencing the national ones,

so long as the ones referenced are appropriate. For mine and quarry blasting, the OSM standard (shown at right) is widely used in the U.S.[2] For non-blasting construction vibration, the Federal Transit Administration standard, along with the related

"Swiss standards", are most commonly cited.[2] For vibration affecting historic structures, the NCHRP report has much

useful information.[2],[36] There are also proposed standards for protection of museums and the artwork contained

in them.[8] Carefully review such vibration standards[2] to understand their value and their limitations. An analysis of some of the most important of these

in the U.S. and abroad can be found in the CVDG's chapter,

Vibration Standards, along with references to them. Links to download free some of the most important can be found in the CVDG's More Information chapter. Existing national standards can be a useful guide in setting local standards. One can even set local or regional standards by referencing the national ones,

so long as the ones referenced are appropriate. For mine and quarry blasting, the OSM standard (shown at right) is widely used in the U.S.[2] For non-blasting construction vibration, the Federal Transit Administration standard, along with the related

"Swiss standards", are most commonly cited.[2] For vibration affecting historic structures, the NCHRP report has much

useful information.[2],[36] There are also proposed standards for protection of museums and the artwork contained

in them.[8] Carefully review such vibration standards[2] to understand their value and their limitations. An analysis of some of the most important of these

in the U.S. and abroad can be found in the CVDG's chapter,

Vibration Standards, along with references to them. Links to download free some of the most important can be found in the CVDG's More Information chapter.

Considerations for Regulating Vibration

While existing standards can be extremely valuable, there are a number of factors which should be considered as potentially relevant to their use in a given regulatory situation. Following is a list of important considerations in undertaking some basic regulation of vibration sources:

- Have a vibration control plan in place for the project. Even if a vibration control plan isn't required in your project, it's a good idea to have one in place. The whole point of a vibration control plan is to

prevent damage and provide guidance for handling damage claims, if they occur. For more on this, see Avoiding Damage. That CVDG chapter has considerable

material which regulators may find valuable.

- Assemble everything that is known about vibration

propagation in the jurisdiction, with particular attention to those variables which can make vibration velocities more credibly predicted (soil type, moisture, underground rock layers and other structures from which vibrations may be reflected). Pay particular

attention to understanding how vibration propagates with distance in the area, as this will have a considerable impact not only on how and what standards are chosen, but the likely radius

of vibration effects and how they are applied in a given case.

- Consider the local built environment one is trying to protect from damage. For example, if the area in question has historic or cultural assets[25],[36] which are irreplaceable, this fact should be recognized by setting lower acceptable

vibration velocities, since such structures are well-known to be more susceptible to damage than most modern construction. Many modern vibration standards and recommendations recognize these differences by setting lower acceptable vibration velocities for

historic and cultural structures.[2],[8],[9]]

Over a million historic structures and locales are listed in the

National Register of Historic Places. The database on its web site is easily searched by city or state. If you find such structures near your project, you

should immediately take steps to monitor and limit vibration, preferably before project start.

- Because some U.S. states (e.g. CA, NH, FL, WI, among others) and municipalities (e.g. New York City) have ground vibration standards in place or have done careful analyses of damage potential, review them for relevance to the

locale of interest.[3], [4]

- Be careful in selecting and using "expert" help. Most "vibration experts" have ties to construction or mining companies, which often bias their views. Understand the background of any

proposed "expert". Give preference to those who have relevant scientific publications. Insist that any expert support his opinion with more than just

claimed "experience"; demand relevant scientific references in support of all opinions offered.

- Base regulatory requirements on examples which are more like the "worst case" than the best case. Because so many factors can influence and enhance vibration amplitudes in structures in any given instance, a "worst case" approach helps

minimize damage, while providing enhanced litigation defense.

- Write the regulatory language with separate discussion of the major vibration sources and separate standards for each. Generally speaking, separate vibration standards should be set for blasting, pile driving, traffic (railway and highway) and construction heavy equipment use, with particular attention to those vibrations caused by ground

impacts of any sort (including impact-like vibratory compactor vibrations and tracked equipment drive-bys). Any heavy equipment operations, including movement of the equipment, to be done within 25 feet of structures should be scrutinized carefully for alternative methods before permitting.

- Embody the regulations in the permitting and contracting process to assure that they accomplish their main function of preventing damage.

- Take into account the past record of a contractor in letting contracts for work. While a few examples of minor damage in a contractor's record should not disqualify a contractor, any examples of

multiple homes damaged or extensive damage should be reflected in the scoring system used to award contracts. Don't depend on the contractor for truthful reporting of such information. Search the Internet for records of

actions against any contractor who may be awarded a contract. If the contractor causes damage, the sponsoring entity will have to pay more, either through settlement or litigation costs.

- Provide guidance on how to mitigate vibrations and prevent damage within the regulations or as an appendix to them.[3],[4] For example,

vibratory compactors

are the most common source of damage in reports to Vibrationdamage.com. Yet, simply substituting oscillatory compactors for vibratory compactors can decrease ground vibration velocities by 75-85%, while providing greatly

improved

compaction efficiency.[21] The CVDG's Avoiding Vibration Damage chapter and the CVDG Pro's Mitigating Vibration chapter have many other simple suggestions for decreasing vibration and damage which can be implemented at little or no additional cost.

Many contractors are responsible and will follow

best practices,

if given the opportunity and the knowledge.

- Mandate at least an exterior pre-construction survey for structures within 100 feet of any project which will involve blasting, vibratory compaction, pile driving or demolition by other than normal and approved

methods. That survey should not be of the "walk-by" or "drive-by" type, as such surveys rarely produce sufficiently detailed documentation of structure condition to be of more than extremely limited value. For projects

where the damage potential is high (e.g. structures less than 25 feet from pile driving, compaction), a complete interior and exterior survey should be done.

- Some unnecessary and highly damaging construction procedures should be banned: pounding on pavement with various pieces of non-qualified heavy equipment for demolition,[26]

driving tracked heavy equipment for more than 10

seconds or 50 feet at a time, using vibratory compactors within 15 feet of structures, and any use of any heavy equipment which violates Operator's Manual instructions for that equipment, directly causing damage.

Such bans should be accompanied with

steep fines, since the procedures they would forbid almost always lead to extensive and costly damage to multiple structures.[11] Most large contractors

already have internal policies banning many or all of those procedures. A fine of $10,000 per violation occurrence is justified, given that relatively minor damage to even one structure

typically will cost in that range to repair. Case-by-case exceptions to such rules may be granted under the regulations prior to work start under well-considered, vibration-monitored and

properly supervised conditions.

- Perform daily exterior damage inspections during the construction of the closest and most sensitive structures to limit damage and gain information to prevent damage to other structures. If damage is found, require stopping

or moving of construction work until the cause is identified and remedied.[23]

Setting standards, while a good first step, is not enough, by itself, to satisfy the need or prevent damage. Good standards must be accompanied by requirements which ensure enforcement of the standards, if they are to have any

positive effect. Keep in mind that structures, once damaged, require lower vibration standards and velocity limits for subsequent work.[29] Setting standards, while a good first step, is not enough, by itself, to satisfy the need or prevent damage. Good standards must be accompanied by requirements which ensure enforcement of the standards, if they are to have any

positive effect. Keep in mind that structures, once damaged, require lower vibration standards and velocity limits for subsequent work.[29]- At a minimum, requirements for construction with heavy equipment should include on-site professionally-supervised vibration monitoring. It should be done by a certified vibration monitoring contractor and located at the

point on adjacent property closest to the work, for any operation involving pile driving,

compaction, pavement demolition or any operation involving repeated ground impact (e.g. demolition). You must verify that it is carried out, as contractors often ignore contract provisions requiring monitoring. That monitoring should be set up to provide real-time feedback to the construction crews, so that they can stop or modify violating

actions as they occur (see photo at right for an example setup with a vibration-triggered alert light). While an argument can be made for requiring vibration monitoring during all working periods, paying special attention to the operations

mentioned should provide good protection at minimum cost. Beyond monitoring these particular operations, all operations done within 25 feet of structures should be monitored for vibration for as long as the operation is within

the 25 foot radius.

- Vibration frequency distribution (from FFT analysis) must be taken into account in assessing vibrations, not just the peak particle velocity (PPV).[19] Most modern standards take the greater damage potential of lower frequencies into account by

setting lower allowable PPV's at lower frequencies. Caution is advised when considering frequency effects, since even blasting vibration of very short duration is known to produce amplification of ground vibrations by as much as a

factor of eight in the home vibration (see Resonance/Fatigue for more on this). This amplification can take a nominally "safe" ground vibration and turn it into an unsafe house

vibration, especially in the far worse situation of long duration construction vibration.

- Be mindful that statistical probabilities for multiple separate events are additive. Ten separate identical vibration events (i.e. having the same PPV and frequency distribution), each with

damage probabilities of 5%,[38] have a combined damage probability of 50%,

assuming that each succeeding

event still has the same 5% probability of damage (see Vibration and Damage for more discussion). All this may not sound very important, but consider,

for example, that a vibratory compaction operation in a single lift of paving would be expected to produce 20-30 similar peak particle velocity vibrations. Vibration PPV's increase with each successive lift. The overwhelming majority of paving jobs involve multiple paving

lanes and lifts. A low single event probability of damage can become an unacceptably

high risk of damage as a result of repetition in construction work.[15] This argument does not take into account the additional effect of the much longer durations of

most construction vibrations relative to blasting vibration, making them still more problematic.[27]

- Monitor the job to make certain that contract provisions regarding preconstruction surveys, vibration monitoring and vibration mitigation are actually carried out on site. Mostly, this involves simply asking to see

evidence of their accomplishment and having someone spend an hour or so checking the evidence. Since some contractors routinely ignore such provisions, their completion should not be left to chance or the word of the

contractor.

- Establish a reserve fund, perhaps taken from the contractor's completion bonuses, for every project. If the project completes successfully, without damage claims 30 to 90 days after completion, it is dispersed, with

interest, according to the construction contract. If not, it can be withheld and used to pay legitimate damage claims, without the expense of litigation. Having such a fund in place will provide incentive for contractors to

carry out their work responsibly. In most places, the current "incentives" for on-time completion act to do just the opposite.

- Investigate damage around a construction job thoroughly and ascertain the cause with as much real scientific data as possible. Avoid clearly scientifically false biases and misconceptions (see CVDG Pro chapter of

same name) like "construction can't cause damage",[20] so often offered by those associated with construction.

Regulators may also find the information in the CVDG chapter, Avoiding Vibration Damage, relevant to their considerations, even though it is written primarily for project sponsors and

contractors.

Vibration Velocity Estimations  Vibration

attenuation equations are often used to estimate vibration velocities from known or reference data,[16] using multiple explicit and implicit assumptions about the variables affecting vibration propagation. The

calculated velocities are then compared to some standard, too often improperly chosen, to provide "proof" of vibration safety. Unfortunately, because meaningful validating data are only very infrequently available for a given locale,

such calculations often do not accurately predict vibration velocities or assess damage potential. Our chapter, Vibration and Distance, provides an introduction to such calculations, with illustrative diagrams of the calculated decrease of vibration with distance for various equipment types and soil conditions. Full-sized versions of several calculated velocity and safe distance plots of the type shown on this page can be

downloaded as a single free PDF

by registered CVDG (free or Pro) owners. Vibration

attenuation equations are often used to estimate vibration velocities from known or reference data,[16] using multiple explicit and implicit assumptions about the variables affecting vibration propagation. The

calculated velocities are then compared to some standard, too often improperly chosen, to provide "proof" of vibration safety. Unfortunately, because meaningful validating data are only very infrequently available for a given locale,

such calculations often do not accurately predict vibration velocities or assess damage potential. Our chapter, Vibration and Distance, provides an introduction to such calculations, with illustrative diagrams of the calculated decrease of vibration with distance for various equipment types and soil conditions. Full-sized versions of several calculated velocity and safe distance plots of the type shown on this page can be

downloaded as a single free PDF

by registered CVDG (free or Pro) owners.

The

attenuation equations can be quite useful where the local soil and geological environment has been thoroughly studied and the attenuation of the vibration

with distance is well-understood. However, vibration attenuation is widely variable from locale to locale,[22] depending on a number of factors. In addition, the simple propagation equations typically used do not take into account the changes in propagation in

different soil and basement rock types nor can they adequately account for varying degrees of fracturing of surface rocks.

All these variables affect

vibration propagation through changes in the exponent value in such equations. All these variables affect

vibration propagation through changes in the exponent value in such equations. At right are shown some calculated "safe distances", for each structure Class defined in the Swiss and FTA standards as a function of the

equipment used.[2],[24] As the attenuation exponent changes, the safe distance can change dramatically, with higher velocity

vibrations from heavy equipment affected far more than lower velocity ones. The range of exponents shown in the diagram reflect the measured values for the exponent derived from vibration measurements in localities around the

world. The safe distance dependences are discussed in much more detail in the CVDG Pro chapter, Calculating Vibration Amplitudes.  Those who wish to calculate

minimum estimated velocities and safe distances (with no safety factors) for their own construction operation

or blasting vibration situation can download our Vibrationdamage.com Ground Vibration PPV and Safe Distance Calculator, available free to registered CVDG for Homeowners and CVDG Pro owners from the direct links in their

Vibration Estimation Tools chapter. Those who wish to calculate

minimum estimated velocities and safe distances (with no safety factors) for their own construction operation

or blasting vibration situation can download our Vibrationdamage.com Ground Vibration PPV and Safe Distance Calculator, available free to registered CVDG for Homeowners and CVDG Pro owners from the direct links in their

Vibration Estimation Tools chapter. Propagation equations rarely, if ever, account for

localized vibration reflection, refraction and interference effects from structures and concrete installations around them, which can cause significantly different velocities to be recorded at identical

distances from the source.[10]

The most advanced approaches for calculating vibration peak velocities, which directly account for local geology by empirical validation, still show significant differences with respect to measured values.[12]

Even differences in landscaping from property to property can affect the ground vibration velocities observed near the structures on those properties.[13] Ironically, towns and cities, where vibration propagation equations are most frequently used

to establish "safe" vibration levels, are the environment where calculations would be expected to be least reliable overall. Saying that the calculation was accurate for measurements at a given location is of little comfort when vibrations

of twice that velocity or greater can occur a couple of houses away the same distance from the same operation.[10] Some examples of factor of two variations of vibration velocities higher than calculated values in a real-life road reconstruction use of vibratory

compactors are given in the CVDG Pro's Calculating Vibration Amplitudes chapter. Extensive damage was done to many homes in those cases. As discussed briefly in the CVDG chapter,

Vibration and Distance, vibration velocities are affected not only by variable propagation of vibration through the ground, but by differences in source energies from equipment model to

equipment model, operator to operator, and run to run. For these reasons, monitoring done after a damage report is almost always questionable in several ways. There is simply no substitute for vibration monitoring done as the job

is occurring at the site of interest. Thus, such vibration propagation equations, while valuable, cannot be used with absolute assurance of accuracy in the absence of a careful study of the local ground vibration

environment, specific to the type of vibration source expected (e.g. construction vs. blasting vs. transport, etc) and/or careful choice of propagation equation parameters to reflect conservatively that environment. Vibration

velocity calculations - and representations of "vibration safety" based on them - should only be viewed as

approximate, at best,

in the absence of proper validation in the specific locale of interest. When such equations are used in an effort to prevent damage, a "safety factor" of at least 2 should be included in the calculated velocity and corresponding "safe

distance".[14],[15] The limitations of vibration propagation calculations are discussed in more detail in the CVDG's Vibration and Distance chapter and the CVDG Pro's Calculating Vibration Amplitudes chapter.

Footnote 7 of the Vibration Potential chapter of the CVDG describes another documented example in which vibration calculations were far from accurate. Protecting Everyone

Given the statistical nature of vibration damage, no regulation can be seen as certain to prevent absolutely all damage. But, the scarcity of local and state vibration regulations is a major contributor to damage, especially in construction settings.[5]

It doesn't take a great deal of effort or money to institute some basic regulation of vibration sources, which can be effective in preventing most damage, lowering legal costs and maintaining citizen goodwill. By researching, choosing, applying and

enforcing meaningful vibration standards,

regulators can reduce costs to all parties from unnecessary and largely predictable damage,

while providing a measure of litigation protection for contractors. Whether you're a heavy equipment-using contractor, a project sponsor, an insurer or a homeowner, having state or local vibration regulations in place will work in

your interest in both the short and long-term.[28]

[1] Other chapters in the CVDG have many references to scientific work, about which those contemplating setting vibration regulations should know. These can be found in the footnotes to every chapter of the

CVDG, in both the free and Professional versions. The Pro version of the CVDG has a compilation of all cited documents in its Cited Literature section. The overwhelming majority of the documents cited in the CVDG can be downloaded for free, either by following the links to the most important studies on the CVDG's

More

Information chapter or by searching for the document titles in a search engine.

↩

[2] Blasting Standards: OSM Blasting Performance Standards, 30 Code of Federal Regulations, Sec. 816.61

Structure Response and Damage Produced by Ground Vibration From Surface Mine Blasting, D. E. Siskind, M. S. Stagg, J. W. Kopp, and C. H. Dowding, United States Bureau of Mines Report of Investigations 8507 (USBM RI

8507), 1980

Construction standards: Transit Noise and Vibration Impact Assessment, Carl E. Hanson, David A. Towers, and Lance D. Meister, FTA-VA-90-1003-06, May 2006 (Federal Transit Administration's Noise and Vibration

Manual)

High-Speed Ground Transportation Noise and Vibration Impact Assessment, Carl E. Hanson, P.E., Jason C. Ross, P.E., and David A. Towers, P.E., DOT/FRA/ORD-12/15, September 2012 (expanded, updated version of FTA Noise

and Vibration Manual)

Blasting and Construction Standards: Erschütterungen — Erschütterungseinwirkungen auf Bauwerke [Vibrations — Vibration effects in buildings], SN 640312a ("Swiss standard", available in German and French)

Standards for Historic Structures: Construction Practices to Address Construction Vibration and Potential Effects on Historic Buildings Adjacent to Transportation Projects, National Cooperative Highway

Research Program (NCHRP), Project 25-25 (Task 72), Richard A. Carman, September 2012

↩

[3] Many state Departments of Transportation have looked at construction vibration in some detail. The California DOT (Caltrans) has produced a number of useful publications: Transportation- and construction-induced vibration guidance manual, Jones & Stokes.

2004, (J&S 02-039), Sacramento, CA. Prepared for California Department of Transportation, Noise, Vibration, and Hazardous Waste Management Office, Sacramento, CA; Transportation and Construction Vibration Guidance

Manual, Jim Andrews, David Buehler, Harjodh Gill, Wesley L. Bender, California Department of Transportation,

Division of Environmental Analysis, Environmental Engineering, Hazardous Waste, Air, Noise, & Paleontology Office, Sacramento, CA, 2013 (While similarly titled to the previous document, this document is intended by

CADOT (Caltrans) to be "supplemental" to the earlier document and other Caltrans documents).

↩

[4] Ground Vibrations Emanating from Construction Equipment, R. M. Lane and K. Pelham, New Hampshire Department of Transportation, Report # FHWA-NH-RD-12323W, 2012

↩

[5] In the U.S. state of New Mexico, where I live, there are no statewide construction vibration regulations whatsoever, aside from use of the OSM blasting standard, applicable only to construction blasting in

road-building. In New Mexico, there are no statewide specifications for any other construction vibrations. My home municipality has no vibration regulations at all, nor has the widespread damage described in the CVDG resulted in any impetus to put regulations in place. This lack of regulation meant that the

relatively strict FTA standard

became, by default, the only one applicable for construction statewide in New Mexico.

↩

[6] The map graphic depicts damage reports by state and territory for the U.S., Canada and Australia. Reports for other countries are indicated by country only. Most countries have multiple reports of damage; more damage

reports are indicated by increasingly warmer-colored markers.

↩

[7] See Structure Response and Damage Produced by Ground Vibration From Surface Mine Blasting, D. E. Siskind, M. S. Stagg, J. W. Kopp, and C. H. Dowding, United States Bureau of Mines Report of

Investigations 8507 (USBM RI 8507), 1980, p 59, for more on this half-amplitude criterion.

↩

[8] Vibration Limits for Historic Buildings and Art Collections, Arne P. Johnson and W. Robert Hannen, JOURNAL OF PRESERVATION TECHNOLOGY / 46:2-3 2015, pp 66-74; Baseline limits for allowable vibrations for

objects, Wei, W., L. Sauvage, and J. Wölk. 2014. In ICOM-CC 17th Triennial Conference Preprints,

Melbourne, 15–19 September 2014, ed. J. Bridgland, art. 1516, 7 pp. Paris: International Council of Museums.

↩

[9] Repairing historic homes damaged by construction can be more complicated and expensive because historic area designations may require that any changes/renovations be in accordance with the historic nature of the

home or district in which it is located. Any "grandfathered" non-historic elements of the home may have to be remedied when the repair is done. These complications provide even more reason for special care in historic

districts or with historic homes and structures.

↩

[10] During one road reconstruction job, one house experienced a maximum vibration velocity of 0.315 in/sec (cf. calculated FTA vibration equation minimum value of 0.374 in/sec at seismograph), in violation of the FTA Class III standard for timber-framed

homes. A few minutes later, a house one home further along on the same street had a measured vibration of 0.660 in/sec, measured with the same seismograph, essentially the same distance away from the paving operation,

using the same vibratory compactor at the same compaction vibration amplitude. This velocity was over a factor of two higher and in violation of all FTA vibration standards and the USBM RI 8507 blasting recommendations for homes with

plastered walls. Since it is very unlikely that such a large difference can be attributed to geology or equipment use variations under these conditions, it is probable that these differences were due to vibration wave

interference effects. Such effects simply aren't accounted for in most vibration propagation calculations.

↩

[11] These bans are suggested because they reflect procedure violations which have shown up repeatedly in reports from all over the world to https://vibrationdamage.com as causes of damage to structures. Many contractors

already ban some of these (e.g. pounding with excavator shovels to break pavement), usually because they are damaging to equipment, as well as buildings. Others are sufficiently dangerous to structures that their use is already

widely discouraged in certain construction circumstances, e.g. vibratory compaction of pavement on bridges, due to risk of damage to the bridge structure.

↩

[12]

Prediction and Calculation of Construction Vibrations, Mark R. Svinkin, 24th Annual Member’s Conference of the Deep Foundations Institute in Dearborn, Michigan, 14-16 October 1999 (available online)

↩

[13] "It was found that anywhere from an appreciable reduction to an appreciable amplification of the vibrations produced can occur, depending upon the geometric parameters of the shaped landscape involved." Reduction in ground vibrations by using shaped landscapes, Persson, Peter, Persson, Kent, and Sandberg, Göran, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, volume 60, May 2014, pp. 31 - 43

↩

[14] Depending on the degree of empirical validation and the sophistication of the vibration model used in the calculations, the safety factor might need to be higher than two. Locales with known low vibration attenuation

(e.g. many counties in Florida), would require higher safety factors. The factor of two "safety factor" is suggested because the few studies where calculations have been systematically compared to measurements show that the

calculations are often wrong by at least a factor of two.

Taking a more scientific approach to the problem, consider that vibration propagation equations are usually of the general form, A=kEd-n, where A is the

amplitude, PPV, or other measure of vibration intensity, k, a proportionality constant, E, some measure of the relative source energy or velocity at a standard distance and d, the distance from the vibration source. Thus, the

value of the exponent of d in the given area represents how rapidly the vibration decreases with distance. The value of n can range experimentally from near one to almost 2, depending on a number of factors. Since the

value of n is simply assumed (often as 1.5) in most uses of vibration propagation equations, the results can be greatly in error, generally and specifically.

Even when careful validation provides real knowledge of the proper vibration propagation exponent for the locale in question, there is typically a large amount of scatter in the data about the best fit line when such

equations are plotted on log-log plots. For example, in a construction blasting vibration example (see Vibration and Distance for the specifics), the

best fit correlation line predicts a vibration velocity of 0.19 in/sec at a scaled distance of 90. While the PPV at one measured location was near this value, 4 others measured at the same scaled distance had values in

excess of 0.4 in/sec. Such validated equations also can't easily account for vibration wave

interference phenomena, which can either increase or decrease the vibration velocity for specific locales the same distance from the source. These calculations are discussed in much more detail in the in the

Vibration and Distance chapter of the CVDG and the Calculating Vibration

Amplitudes chapter of the CVDG Pro.

↩

[15] The need for a "safety margin" is further illustrated when we think about what vibration standards often really mean. Many, like the USBM RI 8507 limits, are based on two standard deviation error limit calculations of damage probability

(see Vibration and Damage for more on this), sometimes with a

safety factor built into the standard. At two standard deviations or 95% confidence, 5% of a large sample of homes would be expected to fall outside the standard (i.e. damaged), as a result of normal statistical variation. In a typical urban road construction job,

with vibrations of a PPV

meeting a 95% probability of non-damage standard, anywhere from 100

to 300 homes might be found along the path of the construction. Thus, we would expect, statistically, damage to between 5 and 15 homes from statistical variation, assuming that all the proper procedures, regulations and limits were followed. Damage to

that many homes would probably be considered unacceptable from a litigation risk standpoint, if from no other.

↩

[16] "Although the table gives one level for each piece of equipment,

it should be noted that there is a considerable variation in reported

ground vibration levels from construction activities.", Federal Transit Administration's

Noise and Vibration Manual,

p. 12-12

↩

[17] Structure Response and Damage Produced by Ground Vibration From Surface Mine Blasting, D. E. Siskind, M. S. Stagg, J. W. Kopp, and C. H. Dowding, United States Bureau of Mines Report of

Investigations 8507 (USBM RI 8507), 1980, p. 33, et seq.

↩

[18] Ibid., p. 44

↩

[19] Although such FFT data are readily available from analysis of vibration monitoring data with the standard software for most digital seismographs, most vibration technicians rarely generate or examine the FFT-derived

vibration frequency distributions, leading to much confusion

about the true vibration frequencies. The technicians usually depend on inaccurate, single, zero crossing frequencies, which are most inaccurate when the vibration frequency distribution is broad and most

dangerous to structures.

↩

[20] The Travelers Insurance Co. offers an online app for its contractor policy holders called ZoneCheck, which allows contractors to calculate what are claimed to be likely vibration interaction distances for various types

of construction. Its accuracy, calculation methods and validation are unknown for the urban environments explicitly illustrated in a video describing it at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h3B5e8bMvQQ. The first line of the narration of that video is, "You already know all about how ground vibration can cause damage to surrounding structures..."

↩

[21] See, for example, Ambient vibration of oscillating and vibrating rollers, J. Pistrol, F.

Kopf, D. Adam, S. Villwock, W. Völkel, Vienna Congress on Recent Advances in Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics 2013 (VEESD 2013), C. Adam, R. Heuer, W. Lenhardt & C. Schranz (eds) (available online)

↩

[22] There can be considerable variation in vibration propagation from location to location in the same town. For example, in the case of one medium-sized city in the western U.S., the vibration attenuation exponents

obtained in various locations within the town varied

from 1.0 to over 1.7. This wide

variation was attributable generally to variations in soil types, varying surface rock geology and varying degrees of natural fracturing of that surface rock. Not all

towns and cities will show this much variance in vibration attenuation, but, without actual vibration measurements at the site of interest to validate calculations, there can be little assurance that calculated velocities are accurate.

↩

[23] Such daily inspections have been advocated by other scientists, as well: Soil and Structure Vibrations from Construction and Industrial Sources, Svinkin, Mark R., International Conference on Case Histories in

Geotechnical Engineering. 8. (2008), p. 12 (available online)

↩

[24] Safe distances are calculated from the FTA propagation equation for construction equipment use by algebraically rearranging the equation to solve for the distance, D, setting PPVequip equal to the

FTA Class III limit of 0.2 in/sec and PPVref equal to reference values for the equipment types shown on the diagram. These parameter values were chosen as most appropriate for construction vibration affecting

homes. Different reference values for different equipment would provide different safe distances as a function of the exponent.

↩

[25] A formal designation of homes and other structures as "historic" or "cultural" assets, may well recognize, and add to, the perceived value of that asset. However, historic designation, by itself, is

not a relevant criterion in determining the resistance of a structure to vibration damage and the vibration limits which should be set for it. The damage resistance criterion must be set by a consideration of the nature of the structure itself (e.g. age, building methods used, foundation

type, wall structure, interior and exterior finishes, condition, etc.). A home built on a rubble foundation is going to be more prone to damage than one with modern slab-on-grade construction. Thus, older neighborhoods will generally

be more sensitive to damage. A careful pre-construction survey can give valuable guidance in setting vibration limits for work in neighborhoods whose structures may be particularly fragile. In the absence of a complete

interior and exterior preconstruction survey, FTA/Swiss limits of 0.12 in/sec should be used as a default ground PPV standard.

↩

[26] While there are no known published measurements of ground vibration velocities from powered excavator pavement pounding, one paper provides velocity/distance data for unpowered

dropping of a 1.5 ton steel ball (approximately equivalent in weight to a granite boulder about 3 feet in diameter) a distance of ten feet. The recorded velocity at 40 feet was 2 in/sec (ten times the FTA Class III standard for homes of 0.2 in/sec). This is comparable to the velocity recorded for

a 1 pound dynamite explosion at the same distance (2.5 in/sec) and is higher than any other non-blasting construction operation, including pile driving. The recorded velocity at 25 feet (the FTA reference distance) was 3.5 in/sec. Such

velocities are consistent with the widespread damage observed around sites of excavator pounding. They also explain why damage is often seen near sites where rock is being dropped (e.g. as rip-rap along water courses to

limit erosion). See: Construction vibrations: State-of-the-art, J. F. Wiss, Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division,

American Society of Civil Engineers, 1981, 107(2):167–181

↩

[27] The assumption of statistical independence of vibration events may not be strictly true, due to the operation of fatigue effects, which make the structure progressively more prone to

visible damage. Fatigue effects are usually quite small in single blast situations. They are likely to be larger in construction settings, where we have shown that total vibration exposures range from tens to hundreds of

times that of "typical" amounts of worst-case blasting (2.0 in/sec PPV) in the same time period, due both to the much greater duration of construction heavy equipment vibrations and their repetitive nature (c.f.

40-60 vibratory compactor

passes in a typical road construction scenario of paving two lanes of traffic in two layers of pavement each, plus compaction of the base). (see

Resonance/Fatigue for more on this matter). Another effect, working like the fatigue effect to increase probability of damage with

repeated application of compaction, is the well-known phenomenon of increasing observed PPV, as soil progressively compacts. See, for example, Ground Response to Dynamic Compaction, P. Mayne, J. Jones and J.C.

Dumas., ASCE Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, Vol 110, No 6 June 1984, pp 757-774.

↩

[28] In over 1600 damage instances worldwide reported to Vibrationdamage.com to date, not a single report has indicated that the contractor, project sponsor or the project insurer willingly paid for any part of the damages. Many such reports include

explicit mentions that the parties responsible for the project have refused outright to reimburse the owner for the damages. While there are undoubtedly a few examples, unknown to us, where claims have been resolved amicably and

fairly, this

large number of examples where responsibility for damage was apparently skirted suggests the possibility of a widespread pattern of evasion of responsibility when contractors cause damage to homes and buildings.

↩

[29]

"Therefore, for freshly renovated buildings and buildings in a poor condition a reduction of the limiting values is necessary. From experience it is known that such buildings have

effectively a reduced stiffness and thus in the standard they are put in the next lower category." Swiss Standard for Vibrational Damage to Buildings, J. Studer and A. Susstrunk, Proceedings, X. Int. Conf.

ISSMFE, Stockholm, Vol 3.,

p. 309

↩

[30] A qualitative estimate of the damage probability, applicable to the Swiss standards for construction vibration damage, has been published: "For peak particle velocities twice as high as the

given guide values damage is to be expected." Swiss Standard for Vibrational Damage to Buildings, J. Studer and A. Susstrunk, Proceedings, X. Int. Conf. ISSMFE, Stockholm, Vol 3., p. 308 (1981)

↩

[31] The situation is worse even than this comparison might indicate. The Swiss standards use the peak vector sum, rather than the peak particle velocity used in the U.S. FTA standard, as the criterion

for acceptable velocities. When the PPV values in each vector are nearly the same, the PVS is a approximately a factor of 1.7 higher than the PPV, limiting the individual vector PPV's to correspondingly lower values. ↩

[32] A now-dated compilation of cities, states, provinces, and countries having blasting vibration regulations is: Blast Vibration and Seismograph Section Report,

International Society of Explosives Engineers, 2003G Volume 1, Appendix 3, p. 11; a formal paper of the findings appeared as: A Survey of Blasting Vibration Regulations, L.C. Schneider, Fragblast, International

Journal for Blasting and Fragmentation, Volume 5, 2001 - Issue 3, pp. 133-156

↩

[33] Road construction is the most commonly claimed source of damage by correspondents to Vibrationdamage.com. Yet, according to our own survey, only five states (NH, NM, VT, NC and FL) embody

vibration limits for construction blasting in their standard specifications for highway and bridge construction. Only two states, FL and VT, include construction vibration limits in their standard specifications. In the

few cases where states set limits, they are all based on blasting standards, not construction ones, with limits ranging from 0.5 to 0.75 in/sec. A number of additional states require blasting plans and/or vibration monitoring in

their standard specifications, but the velocity limits are fixed on a case-by-case basis or established outside the specifications documents. A larger number of states mandate limits for blasting vibration from mining

activities, almost always citing the U.S. OSM or RI 8507 limits. See just above.

↩

[34]

Man-Made Vibrations and Solutions, Massarsch, K. R., International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering.6., 1993, p. 1394

↩

[35]

"The relatively short duration (impulse-type loading) of blasting vibrations does not lead to any important resonant effects in building components. However, with periodic excitation due

to pile-driving, vibrators and traffic considerable resonance effect is sometimes possible." Swiss Standard for Vibrational Damage to Buildings, J. Studer and A. Susstrunk, Proceedings, X. Int. Conf. ISSMFE, Stockholm, Vol 3., p. 308 (1981)

↩

[36] Projects which may affect structures of historical interest must be especially carefully vibration monitored, as historic structures demand lower vibration limits (as low as 0.05

in/sec up to 0.12 in/sec). You can search the

National Register of Historic Places database to find individual sites and general locales which are along the route or in

the area of a planned project. This is most easily done by searching for the city or

county of interest. Note that even historical structures which are not on the National Register of Historic Places are subject to the Section 106 review process, if they meet the standards for inclusion in the Register.

Unnecessarily damaging a historic structure by construction vibration is one of the most direct routes to litigation that exists.

↩

[37] "Statistically significant" is defined in this case as the value exceeding two standard deviations (95% confidence level) from the mean.

↩

[38] I have chosen the 5% probability level for this discussion because most vibration limits are set at or near the 5% probability of damage level.

↩ |

|

This is a chapter from the Construction

Vibration Damage Guide for Homeowners (CVDG), a 100+ page free

book with over 300 color photos, diagrams and other illustrations.

It is available at

https://vibrationdamage.com as a series of web pages or in full,

web navigation and ad-free,

as a downloadable PDF e-book, with

additional content not available on the web. The free

version of the CVDG is licensed to homeowners and others for

personal, at-home use only. A Professional Edition (CVDG Pro), licensed

for business use and with over three times as much content, can be ordered from our

Order the CVDG Pro page, usually with same-day delivery. You can comment about this page or ask

questions of the author, Dr. John M. Zeigler, by using our Visitor Comment

form. This is a chapter from the Construction

Vibration Damage Guide for Homeowners (CVDG), a 100+ page free

book with over 300 color photos, diagrams and other illustrations.

It is available at

https://vibrationdamage.com as a series of web pages or in full,

web navigation and ad-free,

as a downloadable PDF e-book, with

additional content not available on the web. The free

version of the CVDG is licensed to homeowners and others for

personal, at-home use only. A Professional Edition (CVDG Pro), licensed

for business use and with over three times as much content, can be ordered from our

Order the CVDG Pro page, usually with same-day delivery. You can comment about this page or ask

questions of the author, Dr. John M. Zeigler, by using our Visitor Comment

form.  If you would like to discuss vibration damage issues and view additional content not found in the CVDG, Join

us on Facebook. Please Like us while you're there. If you would like to discuss vibration damage issues and view additional content not found in the CVDG, Join

us on Facebook. Please Like us while you're there. |

| |

|